Gooseberries: Origins - Consumption - Nutrition Facts - Health Benefits

|

|

|

Contents

- Geographic origin and regions grown

- History of consumption

- Common consumption today

- Nutrition Facts: Vitamins, minerals and phytochemical components

- Health Benefits: Medicinal uses based on scientific studies

- Bibliography

Gooseberries cleanse the digestive system but the green ones can cause a stomach ache when eaten in great volume. My brother found this out when we were children finishing up in hospital overnight. I didn't like the green ones much but when they turned red they were very tasty.

We used to hunt out the big plump red ones, taking care to avoid the prickles. Our mum was very adept at making jams and other treats with both the prolific berries and the black and red currants we had growing in the back yard.

Geographic Origins and Regions Grown

Native to Europe, northwestern Africa and southwestern Asia, gooseberries are included with a number of similar species in the subgenus Grossularia. Many scientists, however, classify it as its own species. The gooseberry grows in diverse places from high altitude thickets and low rocky forests to vestiges of the past.

It is not uncommon in Britain to come across an old abandoned foundation and see a gooseberry bush that is hopefully ripe for the picking. The gooseberry favors high altitudes and cooler temperatures. Easily meeting that criterion, the North American gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) grows abundantly in the northern parts of the United States and Canada.

The sprawling bushes grow between 3 to 10 feet tall with sharp spiny branches. The wild fruit is smaller than that of garden cultivated varieties. The gooseberry’s color varies from green to deep purple or red berries. They also differ from the currant, a similar fruit in the Ribe family, in that the flowers grow on short stems in groupings of one to three and they have spiny stems.

European varieties of the gooseberry include Clark and Fredonia, both of which produce large red berries. The popular American varieties are Pixwell (soft pink half-inch berries) and Welcome (dark shade half-inch berries that are sweeter than the Pixwell).

History of Consumption

The gooseberry is generally more prevalent in Europe than in North America. They are noted as being the most flavorful and produce a larger berry. Once as popular as blueberries, the North American gooseberry faced setbacks due to the federal legislation’s attempt to protect the American forests from disease.

In 1920 Ribes were removed from the forests and gardens and further planting of gooseberry shrubs was banned. By the time state mandated legislation was in place in the 1960s, some generations had no remembrance of this once valued berry. In addition, gooseberries in North America have the misfortune of not being as flavorful. American gooseberries are now crosses between European varieties and native species but still produce a smaller fruit.

One gooseberry bush might yield between eight to ten pounds of fruit. The peel is the tart portion of the berry with its pulp being sweeter. It is picked under-ripe and used for tarts or picked ripe for a variety of sweet desserts. A famous gooseberry recipe is the “fool” which is cream folded into the stewed berries. Other popular forms of consumption include jams, jellies, juices, and liquors.

Common Consumption Today

Gooseberries vary in bitterness, so much so that some varieties cannot be eaten. It is rumored that the higher the altitude, the more flavorful the fruit and most people claim that the European version is tastier than the North American version. In America the gooseberry is making a comeback of sorts. Several varieties of the gooseberry are being grown for their resistance to disease and as a means of improving its flavor.

Edible varieties are good in salads and compliment meat dishes or poultry stuffing. The husk, stems, and tops are removed before the berry is eaten or cooked. Extracts are used in numerous juices and soy beverage compositions to enhance sweetness upon consumption. Pectin makes them perfect for jams and jellies. Despite their long growing season, they are often frozen for future use.

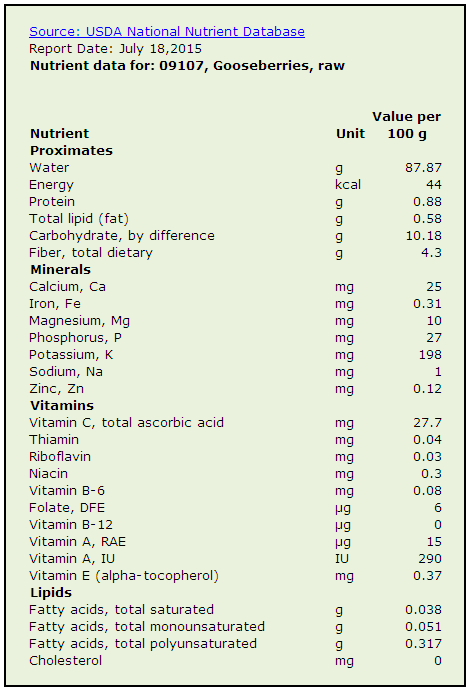

Nutrition Facts: Vitamins, Minerals and Phytochemical Components

Gooseberries are rich in vitamin C, and also contain vitamins A and D. They are an excellent source of calcium, potassium, phosphorus, niacin, iron, and dietary fiber. Most importantly they contain ellagic acid, a component that does not break down during cooking and is a natural cancer-fighting agent (2).

Scientists measure amounts of major anthocyanins (chemical that affects a berries color) and pigment content in order to recommend the best cultivars for harvesting and consumption. It is found that the darker the berry the healthier its benefits (1). The following table data source is the USDA,

Health Benefits: Medicinal Uses Based on Scientific Studies

In the middle ages the gooseberry was thought to have cooling properties to treat fever. North American Indians not only used berries to make a tea to treat colds, but also utilized the leaves, branches, and inner bark to treat colds and diarrhea.

Today the gooseberry shares rank with red wine and many other fruits and berries for their anthocyanin and phytochemical content. Everyday new anthocyanins are discovered. As other berries in this category; they have been noted for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity (3).

A berry that cleanses the digestive system or causes a stomach ache when eaten in great volume such as the gooseberry, is often used during fasting to expel toxins. Studies in Russia show that the unripe gooseberry prevents body cells from degenerating, slows aging, and guards against illness.

Bibliography

1. Jordheim, M., Mage, F., Andersen, OM. (2007). Anthocyanins in berries of ribes including Gooseberry cultivars with a high content of acylated pigments. J. Agric Food Chem. 55(14):5529-35.

2. Stelljes, Kathryn Barry. (1998). A Current Treat for All Seasons; Agricultural Research, a USDA magazine.

3. Wu, X., Gu, L., Prior, R.L., McKay, S. (2004). Characterization of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in some cultivars of Ribes, Aronia, and Sambucus and their antioxidant capacity. J. Agric Food Chem. 52(26):7846-56.

Disclaimer

Nutritiousfruit.com provides this website as a service. Although the information contained within the website is periodically updated, no guarantee is given that the information provided is correct, complete, and/or up-to-date. The materials contained on this website are provided for general information purposes only and do not constitute legal or other professional advice on any subject matter. Nutrtiousfruit.com does not accept any responsibility for any loss, which may arise from reliance on information contained on this website. The information and references in this website are intended solely for the general information for the reader. The content of this website are not intended to offer personal medical advice, diagnose health problems or to be used for treatment purposes. It is not a substitute for medical care provided by a licensed and qualified health professional. Please consult your health care provider for any advice on medications.

Didn't find what you were looking for? Search here...

Amazon Search Box:

Did you like this page?

|

|

|